ANALOGUE and DIGITAL, the eternal challenge

January 25, 2025

The sound of ham

January 25, 2025The complexity of high-fidelity cables

The eternal, unresolved and perhaps irresolvable cable diatribe, with the exhausting and often sterile discussions that ensue, also draws its lifeblood from certain misunderstandings that feed it and do not allow it to be analysed properly

Let us look at these misunderstandings, but not before pointing out the quantities that characterise the context in which we are moving.

Let’s start with frequency extension: the canonical audio band comprises the frequencies ranging from 20 to 20,000Hz, with a ratio therefore of 1 to 1,000 between the 2 band extremes.

Let’s move on to dynamic range: the theoretical dynamic range of a normal 16-bit audio CD is 96dB, with high resolution you can easily reach the useful 120dB, with a theoretical limit approaching 150dB. Considering that at every 6dB increment the signal intensity doubles (every 20dB tenfold) at 96dB we have a ratio of 1 to 63,000, which rises to as much as 1 to 1,000,000 with 120dB (1 to 10,000,000 with 140dB, and so on).

To sum up, we are dealing with signals that vary 1,000 times on the frequency axis and 1,000,000 times on the intensity axis (to be clear, 1 million is the difference between 1mV and 1,000V).

Having clarified that the context is particularly extensive in its dimensions, we can move on to the misunderstandings I mentioned earlier.

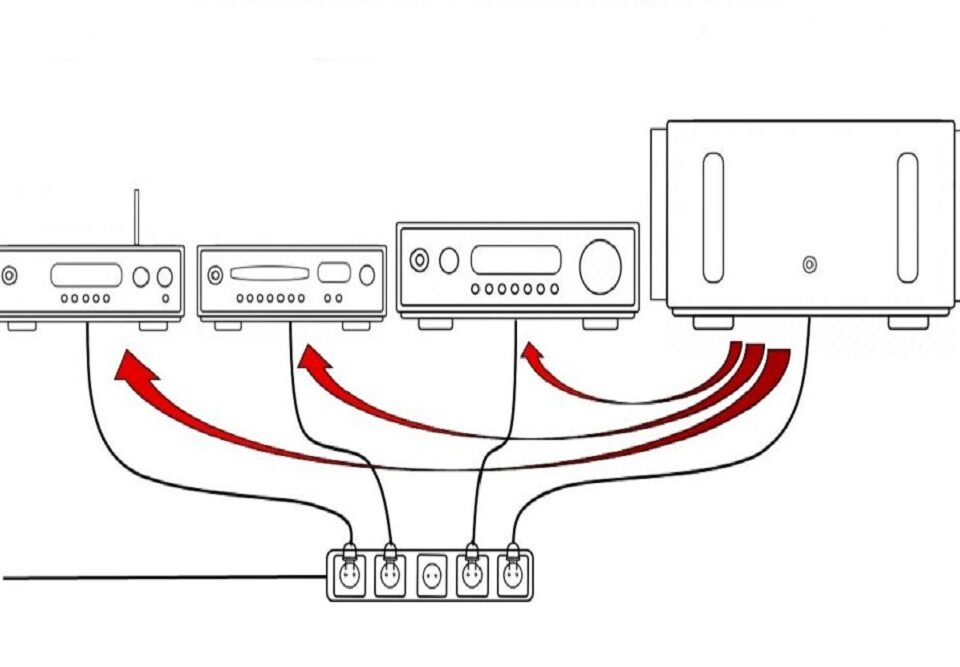

The first misunderstanding: considering the cable as an isolated element and not as part of a system.

In general, a cable is designed to connect two pieces of equipment together, it therefore has a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. Analysing the cable as a single element, without also including in the analysis the equipment that is part of the system, does not appear correct and does not help to understand its operation.

The second misunderstanding: what I cannot measure does not exist.

No one can doubt that measurements, if done correctly in terms of instruments and methodologies, are necessary to describe a phenomenon or behaviour, at least from a quantitative point of view. No serious designer would ever do without a good set of laboratory measurements.

However, it seems that the availability of usable measurements on cables is far from sufficient, thus leaving plenty of room for scepticism and mistrust on the part of many.

On the other hand, we know that research has a very high cost, and we cannot reasonably think that the large manufacturers who lead the market are fumbling around, leaving the success of their projects to chance, without a solid base of objective and repeatable feedback. They have certainly identified tests and measurements in their own laboratories that give them reasonable certainty or at least direct them to the most promising development paths. The fact that this know-how then remains relegated to their laboratories is more than understandable, since it is industrial secrets that constitute their main competitive advantage.

But the question is another: if we really want to have the comfort of measurements, we have to think of a very complex system of measurements, which in addition to the cables also include the devices that are connected to them, because what we will hear at the end of the path, will be nothing other than the consequence of the interaction of all the components in the chain. It will therefore be necessary to measure the effect that a certain cable causes in a certain context, knowing that elsewhere the effect will potentially be different.

Let us come to the complexity.

When approaching the subject of cables, we are instinctively led to focus on the conductors that compose it, restricting our observation to the characteristics of the metals used: purity, treatment, cross-section and length being the main ones.

Another relevant element is certainly the geometry, i.e. how the cable is constructed, with the associated electrical parameters in terms of resistance, inductance and capacitance.

It is more difficult for us to dwell on the other materials found in cables, the sheaths and insulators, which instead have a decisive influence on the overall behaviour of the ‘cable system’. Indeed, it is sufficient to replace the outer sheath of a cable to realise how important it is.

To conclude, I would like to make a few brief remarks to complete the picture representing the complexity of the subject:

– the connecting cables are constantly immersed in magnetic and electromagnetic fields, and are affected by them to a greater extent than those of the internal wiring of the equipment, which are shielded by the container in which they are housed

– shielding with 100% effectiveness is de facto non-existent

– shielding in copper, aluminium and silver works at high frequency but is

rather ineffective at mains frequency (50/60Hz)

– insulators are also dielectrics, placed between two conductors they form

automatically a capacitor

– placing a cable on the floor or any surface increases its

parasitic capacitance and changes its electrical behaviour

– two parallel conductors attract or repel each other depending on the intensity and direction of the current flowing through them: this generates movement, which in turn generates other current. The intensity and time delay of which depend on the cable geometry and the damping induced by the materials used

– all cables are sensitive to vibration

These and other factors, if taken individually, could be considered insignificant, they nevertheless become relevant in their entirety and in the specific context: remember that we are moving in an area whose magnitudes extend by a factor of at least 1,000 in frequency and 1,000,000 in intensity, and that this second figure in particular makes it clear that even apparently negligible elements must be taken into serious consideration.